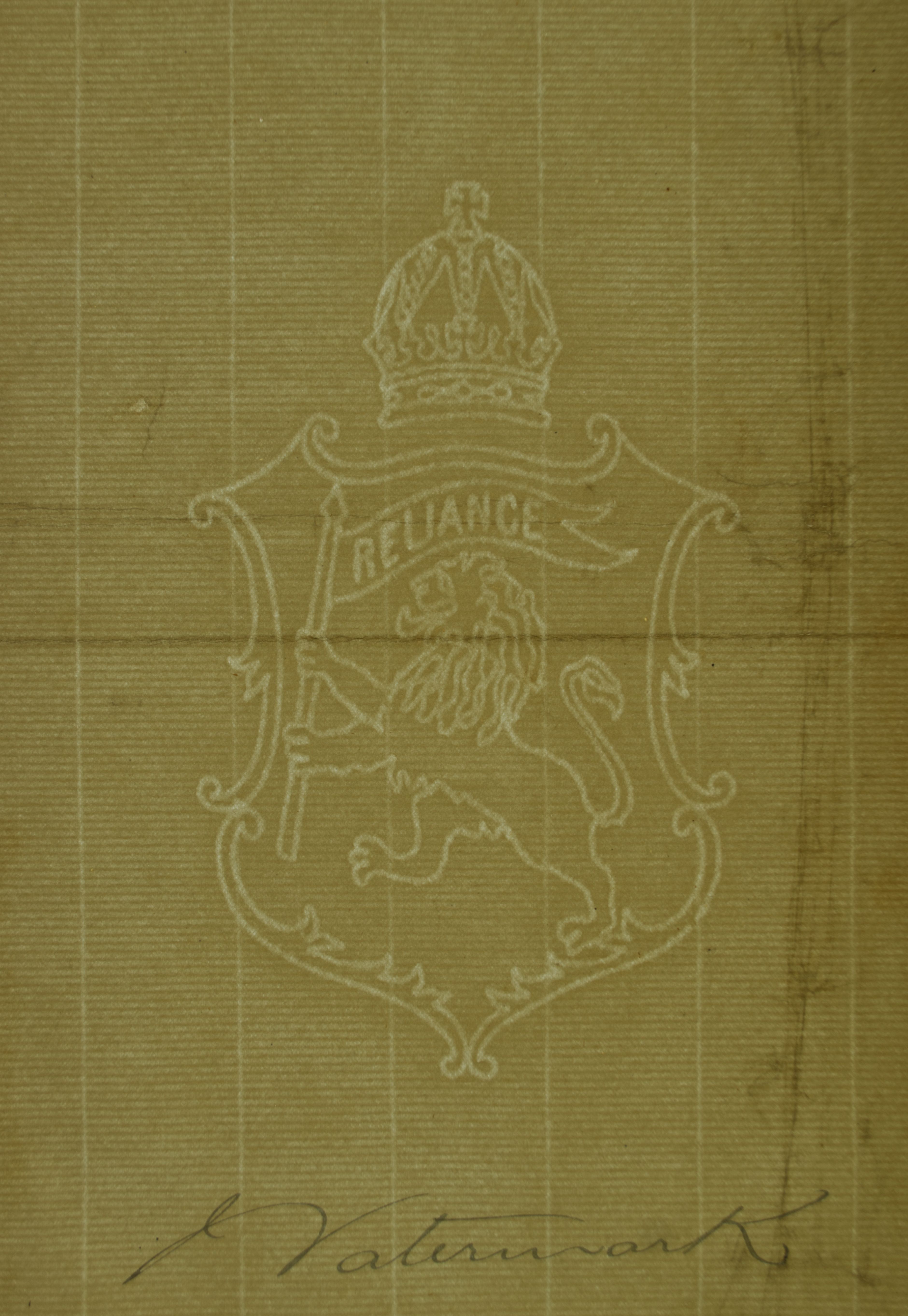

Have you ever held a piece of paper up to the light? A letter, a document, a banknote? You might find a hidden picture, one not visible upon first glance.

You have uncovered the secret of the watermark.

A hidden art, one of light and shade, made within the paper itself. An art form that might easily go unnoticed, often destined to be written or printed over and only spotted by the most trained of eyes.

“The artist in wire, working for papermakers, was surely the most retiring of all our eighteenth-century craftsmen, for it is rare indeed that his work is noted by the public. To discern and appreciate it, it will always be necessary to peer painstakingly through the leaf of paper on which, while still wet, the wireworker’s pattern was imposed as a watermark.”

The first paper came from China. Legend tells that in 105 CE Cai Lun saw wasps building their nests, giving him the idea to make a pulp from plant fibres which could then be transformed into a sheet of paper.

Very gradually the process travelled west along the Silk Road, entering Europe for the first time in 1056 in Spain.

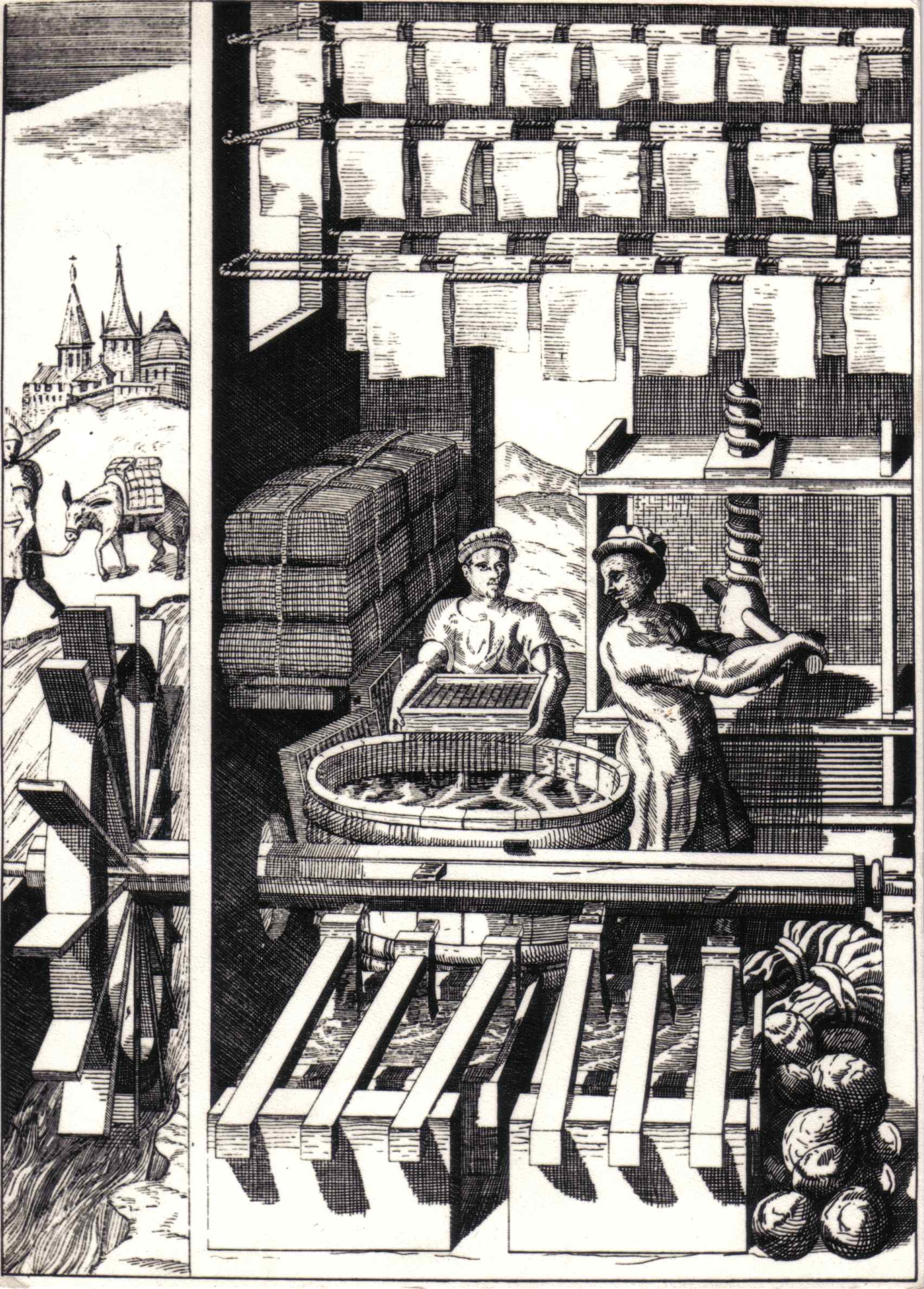

In Europe, rags of cotton or linen would commonly be used, beaten into a pulp and diluted with water that would create a paper stock. When this mix is lifted with a mould, and then couched onto felts, a sheet of paper is formed.

Image: Litho of German paper making process at Nuremberg in 1662 from a book by Georg Andreas Böckler. The print is based upon an earlier image by Strada in the 1550s.

A vat containing pulp is prepared.

The mould, a wooden frame with a wire mesh, and the deckle, a removable frame sitting on top, are submerged into the vat.

The water drains through the wires of the mould to leave a layer of pulp on top. A small shake is given to help align the fibres.

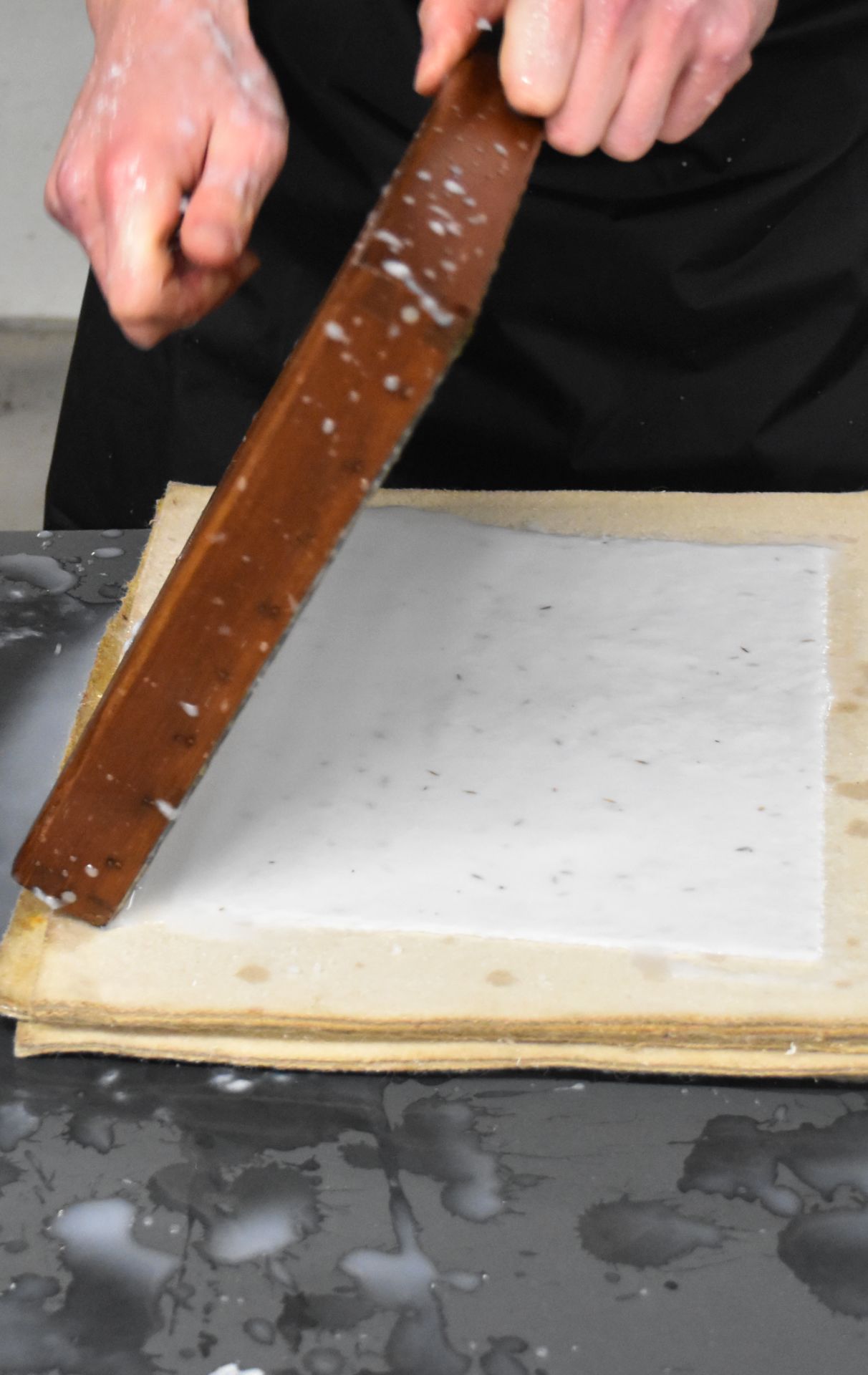

The deckle is removed, and the mould is then upturned and pressed onto felt, a process known as couching...

...and as the mould is taken away, a sheet of paper is left behind.

A pile of sheets on felts, known as a post, will later be placed into a press to squeeze out further water before air drying.

A vat containing pulp is prepared.

The mould, a wooden frame with a wire mesh, and the deckle, a removable frame sitting on top, are submerged into the vat.

The water drains through the wires of the mould to leave a layer of pulp on top. A small shake is given to help align the fibres.

The deckle is removed, and the mould is then upturned and pressed onto felt, a process known as couching...

...and as the mould is taken away, a sheet of paper is left behind.

A pile of sheets on felts, known as a post, will later be placed into a press to squeeze out further water before air drying.

A watermark is born at the same time the paper itself is made.

A metal design is attached to the mould, creating a raised profile over which the pulp fibres will settle. As fibres settle and level to form the sheet, fewer settle upon the raised design. This creates a lighter area within the finished sheet of paper.

The watermark would be stitched onto the mould.

Watermarks such as the Fleur-de-Lys and the crown here were commonly used to indicate the size of the paper.

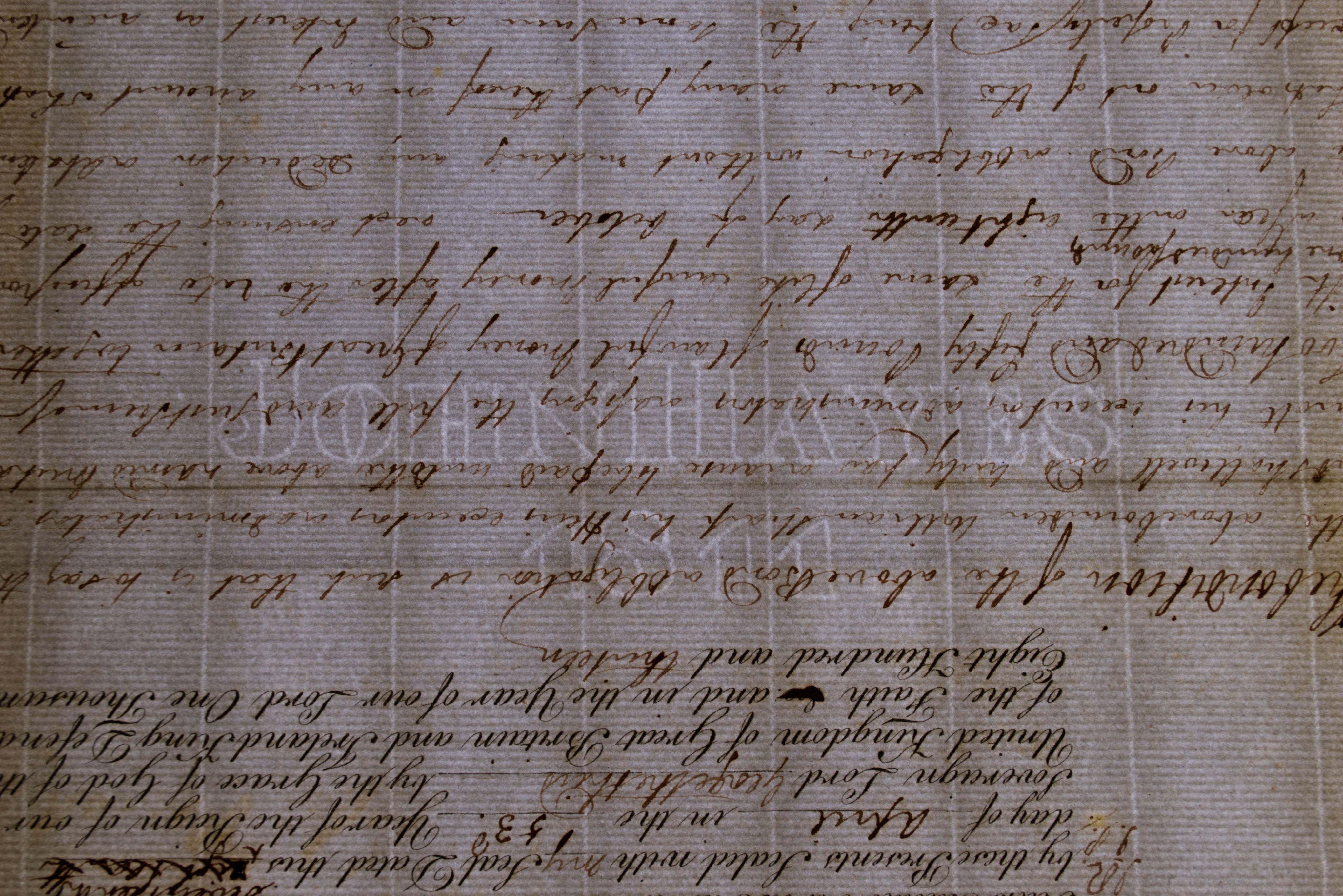

A countermark showing the maker's name and year of production in reverse.

This watermark shows 'G JONES 1806' - showing the maker to be Griffith Jones of Nash Mills.

This particular mould is making 'laid paper', named for the horizontal 'laid lines'.

The thicker 'chain lines' go vertically, following the wooden ribs of the mould.

A watermark is born at the same time the paper itself is made.

A metal design is attached to the mould, creating a raised profile over which the pulp fibres will settle. The raised area will become thinner when the paper is made, creating a lighter area within the sheet of paper.

The watermark would be stitched onto the mould.

Watermarks such as the Fleur-de-Lys and the crown here were commonly used to indicate the size of the paper.

A countermark showing the maker's name and year of production in reverse.

This watermark shows 'G JONES 1806' - showing the maker to be Griffith Jones of Nash Mills.

This particular mould is making 'laid paper', named for the horizontal 'laid lines'.

The thicker 'chain lines' go vertically, following the wooden ribs of the mould.

The first watermarks appeared at Fabriano, Italy, in 1282, over 1000 years after the first paper was made in China. In part this was due to the type of mould used in Europe, where metal wires replaced brittle bamboo. Mould makers could work more delicately with wire to create elaborate designs.

Watermarks proved very important for an expanding industry.

Watermarks gave a way to trademark papers at a time when papermakers were paid for the amount they produced. They gave the name of the maker and mill, and the year the paper was produced – and by doing so becoming a way to guarantee the paper’s quality, and become a form of advertisement.

Watermarks also became a way to indicate the size of a sheet, with symbols such as the Fool’s Cap (foolscap) and the Fleur-de-Lys commonly used.

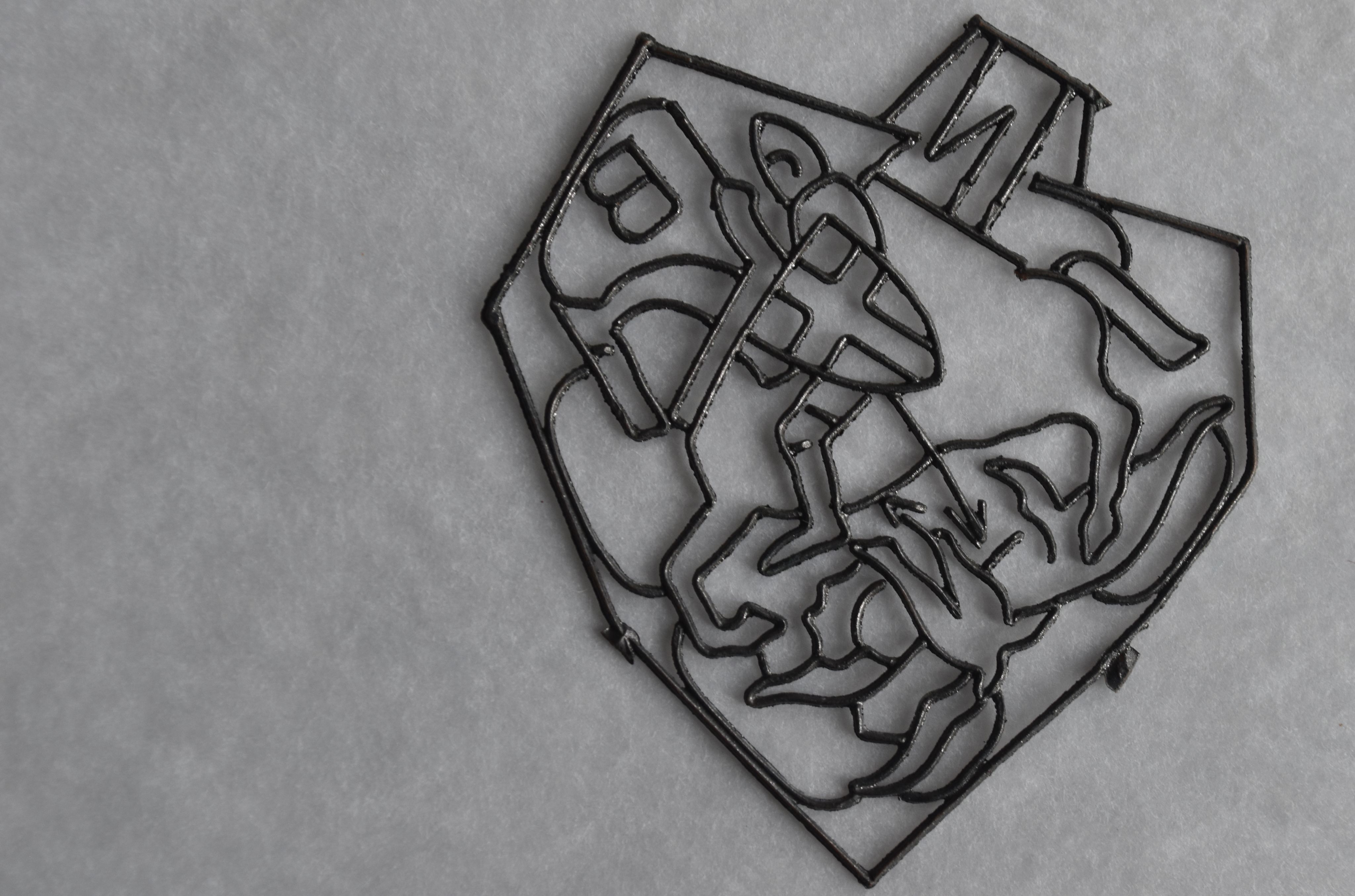

Image: a metal watermark for Sawston Granta Parchment.

Creating a watermark is a delicate art, and one that became more complex over time as papermakers created more and more elaborate designs.

There were many factors for a mouldmaker to consider:

- How would thinner areas affect the strength of the paper?

- How would the design become distorted when the paper was made?

- How would the watermark be attached in a way where it wouldn’t slip on the mould?

Image: a metal watermark for Heron le Press with two figures reading a book.

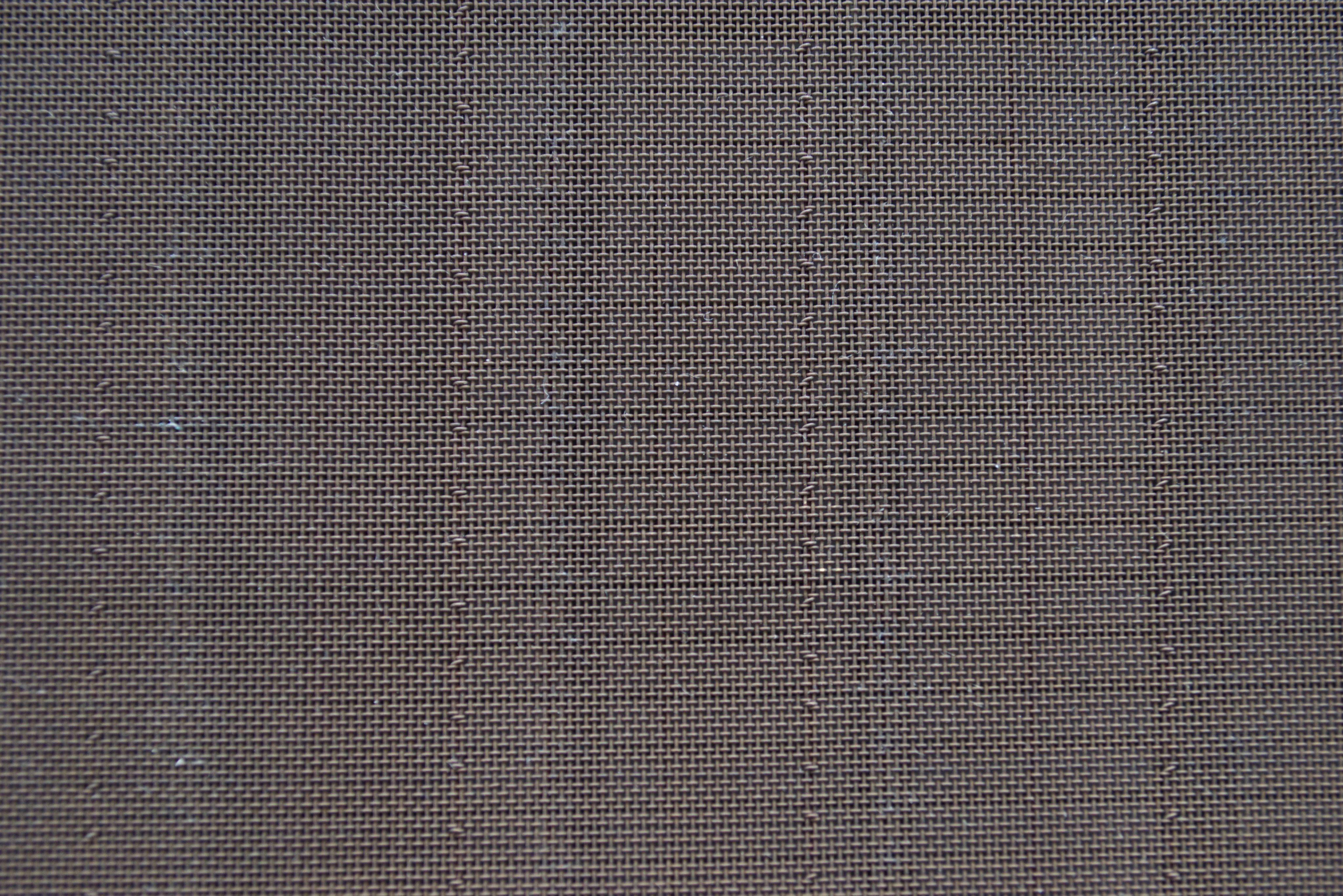

A solution to the last question came with James Whatman’s invention of a new type of mould, the ‘wove’ mould. Previous moulds were ‘laid’, with a lined texture showing the lines of the wires and ribs of the mould below.

The new mould used finely woven wires to create a smoother and flatter surface, offering a finer quality to printers and artists.

The wove surface also allowed watermarks to be stitched or soldered more securely onto the mould, meaning they were less likely to move during the papermaking process.

Image: watermark showing a knight on horseback, carrying a shield

The closely knit texture of a wove mould. Compact woven wires allow for minimal movement when watermarks are stitched onto the surface.

A new type of paper mould emerged. Wider laid lines spaced across the ribs, below the top wire cover, allowed for the elimination of 'shadow zones' that showed the position of the ribs. This created a smoother paper with a more consistent surface.

Compare this with the single screen of the earlier laid mould. Note also the stitching attaching the watermark to the mould.

In 1803, the first ever mechanised paper machine was installed at Frogmore Mill.

The face of papermaking was changed forever.

The Fourdrinier Machine followed the same basic principle as handmade paper, with a ‘wet end’ where pulp settles over a wire. Paper could now be produced quickly and cheaply.

But the first machines were missing something – how could paper made on a machine include a watermark?

The answer came in 1825 with the invention of the dandy roll by John and Christopher Phipps, a roll placed towards the end of the machine wire where a continuous sheet had formed. The roll would press a pattern from its surface into the pulp, which would remain through the further pressing and drying of the paper.

Initially these were made to add a laid pattern onto machine made paper, until then made with wove wires, but it was the same principle that allowed watermarks to be added.

Image: A brass dandy roll with a watermark for T.J. Marshall & Co of London & Dartford.

A dandy roll used by Knowles Trotman Ltd. The roll includes both a watermark design and laid lines.

Many uses for watermarks have been found since their invention. For governments, they could become a way to regulate and tax an important industry, with watermarks being able to show the size of paper, the place of origin, and the year of production.

However, this didn’t always go to plan. In France it was decreed that watermarks must show the year of manufacture, with their legislation giving 1742 as an example. For many years afterwards, paper was made showing the 1742 date that had only been given as guidance.

For historians though, they can prove valuable. In 1907, the Swiss filigranologist (study of watermarks) Charles-Moïse Briquet published his four-volume work, Les Filigranes. His work contained over 16,000 watermarks and their origins dating between 1282 and 1600, and included over 700 dragon and over 500 unicorn designs.

Though not always 100% reliable, a watermark can provide a means to know when a document or book has been produced, and where the paper has been sourced from. A watermark can give proof of authenticity – or sometimes the opposite.

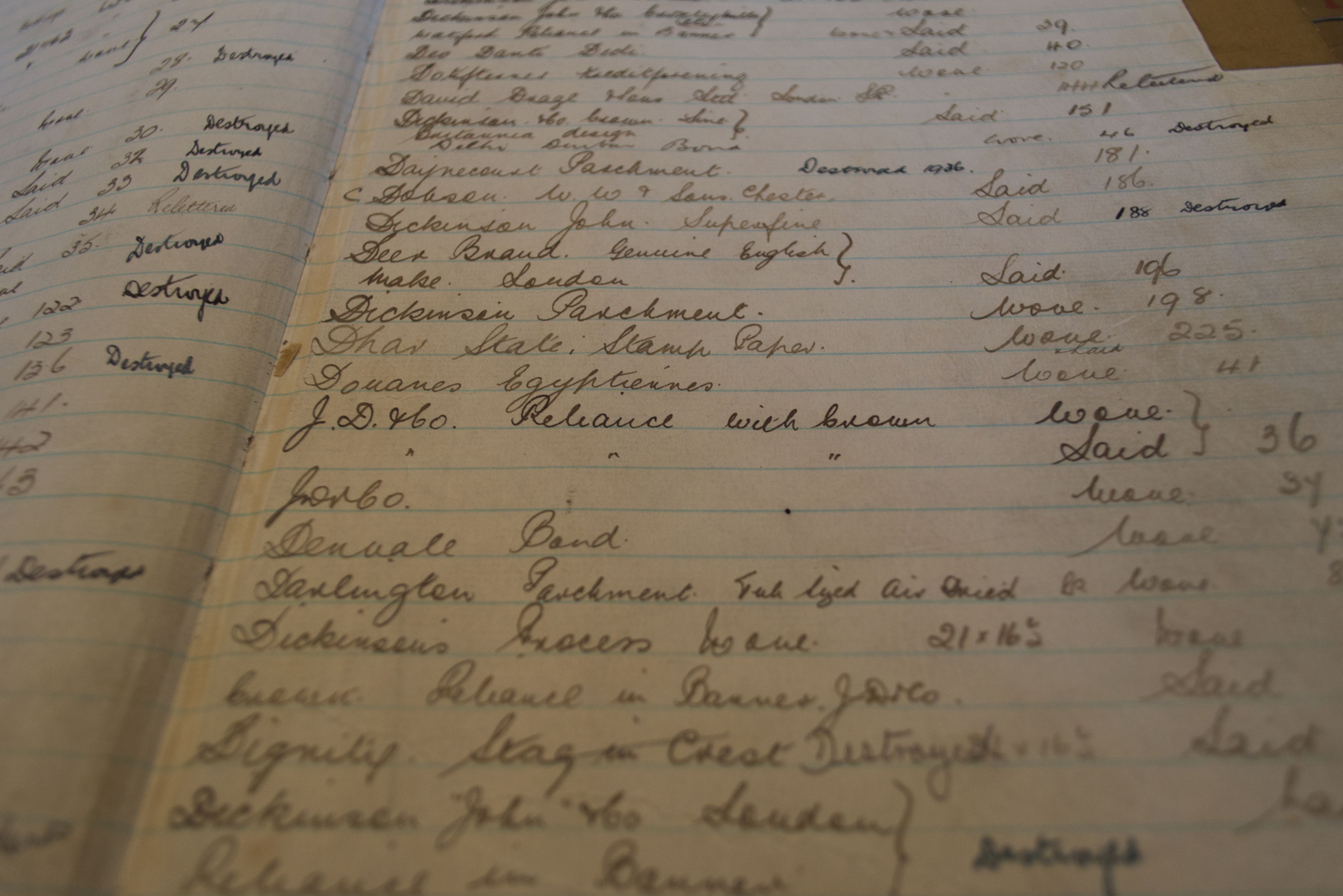

Forgeries have been uncovered with the help of Frogmore's records.

In 2019, a letterpress historian contacted the archive, having received a document claiming to be a report to solicitors about a near miss involving the Titanic in April 1912. Evidence from the printing and handwriting pointed towards the report being a fake, and the last clue came in a watermark: one of Croxley Script, produced by John Dickinson & Co.

Through examination of dandy roll records, it was confirmed that the paper could not have been produced before the 1950s, putting it at least 40 years after the incident it described.

Image: a dandy roll record used by John Dickinson & Co.

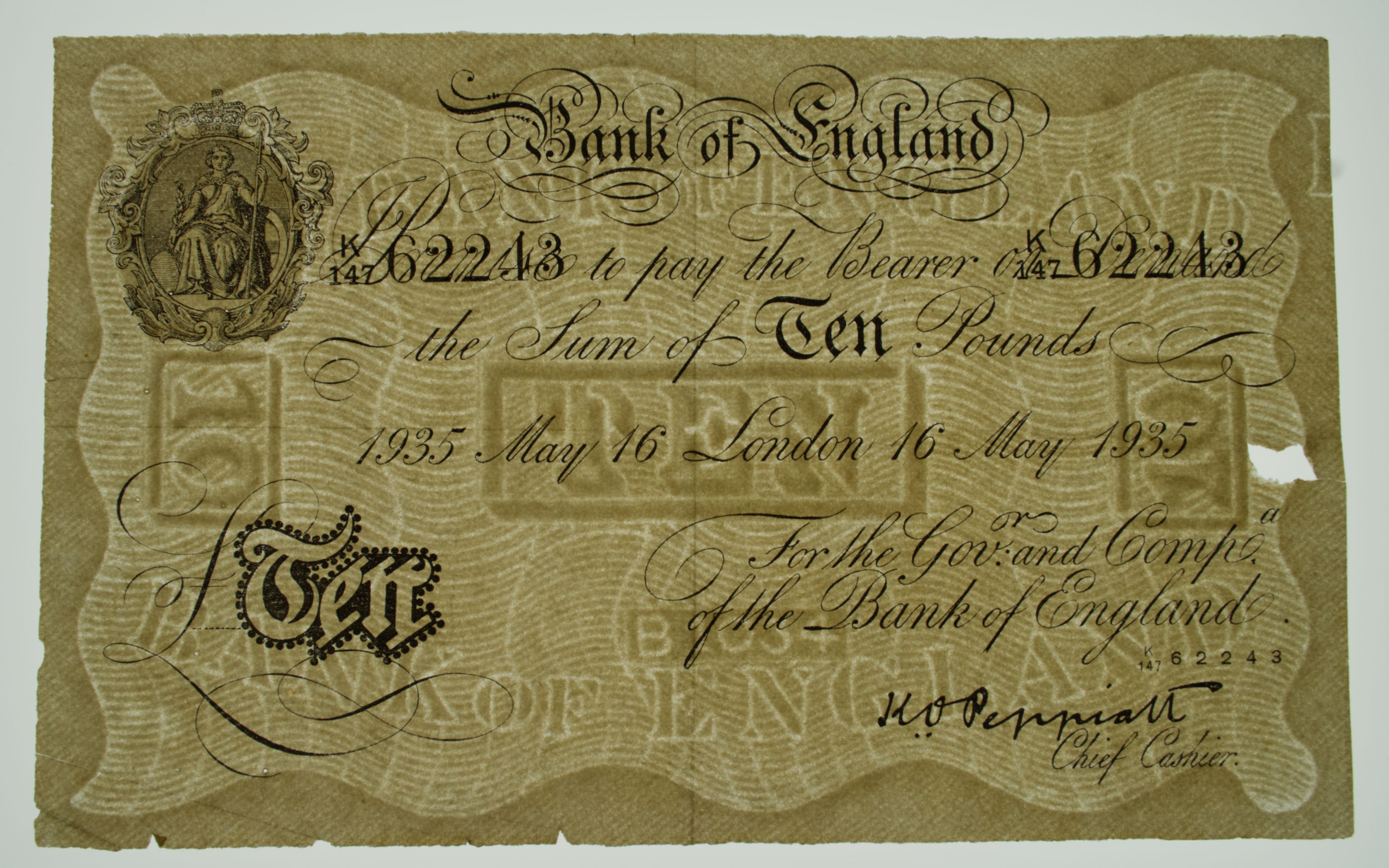

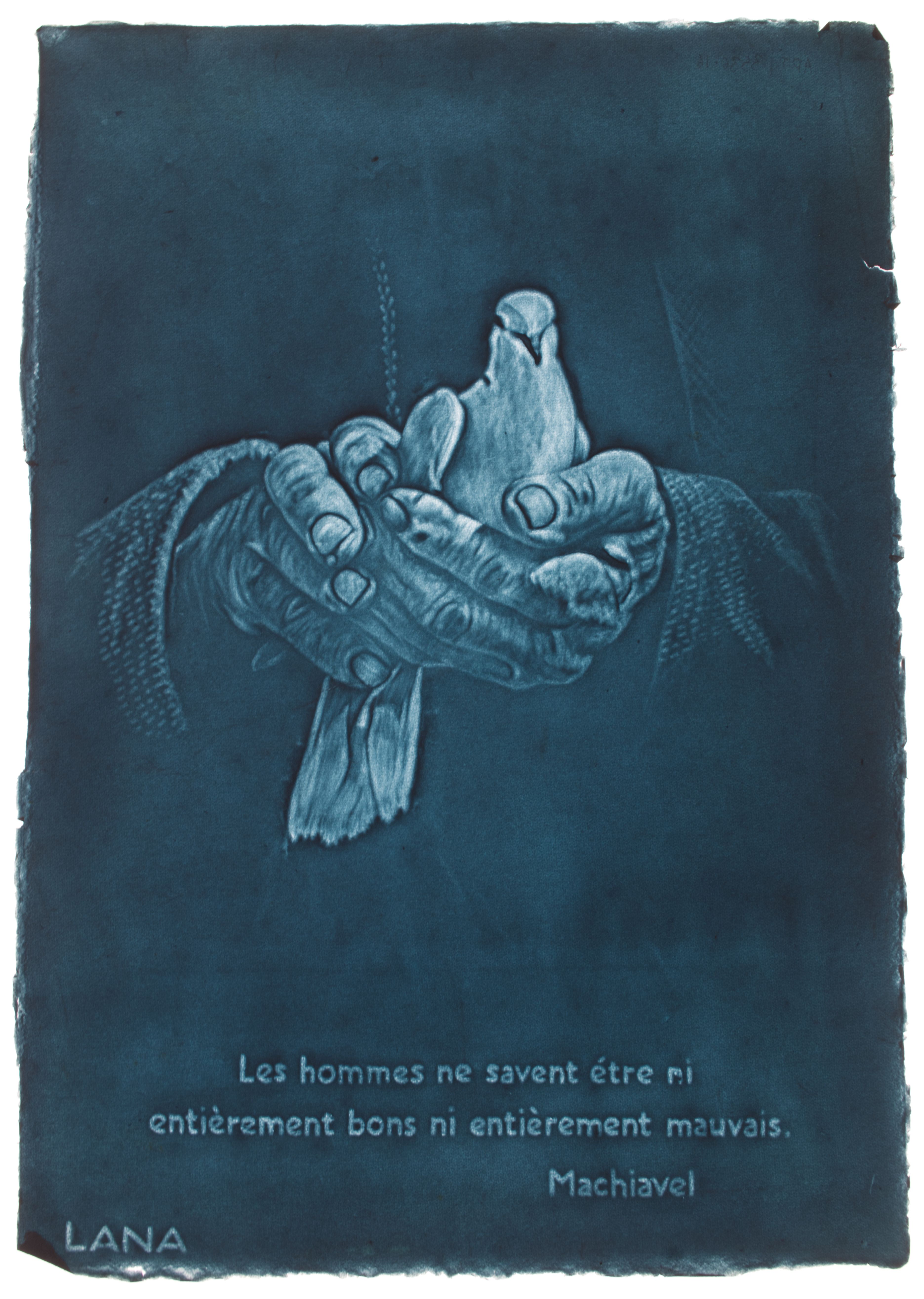

Watermarks offer a means of security in themselves. The more complex the watermark, the more difficult it would be for counterfeiters to copy. As banks moved towards paper currencies in the 17th and 18th centuries, this would become an essential way to fight forgeries.

The complexity of the British banknote had become extraordinary by 1798, as designed by William Brewer. A zig-zag pattern was used – using alternate chain lines pulled in opposite directions to create a series of ‘W’s. Wires were also bent over tubes to create semi-circles and form a ripple effect.

The elaborate design has its downsides though. A pair of watermarks would have 8 curved borders, 16 figures, 168 large waves, 240 letters, 1056 wires, and 67,584 twists – and hundreds of thousands of stitches. Moulds were fragile and would need to be checked constantly to stay in working order. Eventually it became possible to produce these by machine, initially by making a steel die and pressing out the wire profile from it.

But preventing forgery was never truly impossible. The photo shows how complex a Bank of England note was by the 1930s, and yet this is still a forgery. During the Second World War, Nazi Germany produced almost nine million notes as part of Operation Bernhard - an exercise to forge British bank notes and crash the economy.

Image: A British banknote produced by Nazi Germany during Operation Bernhard. Though this note is a forgery, note the complexity of the watermark with its use of curved lines.

New technologies allowed for new innovations in making banknotes and other security papers.

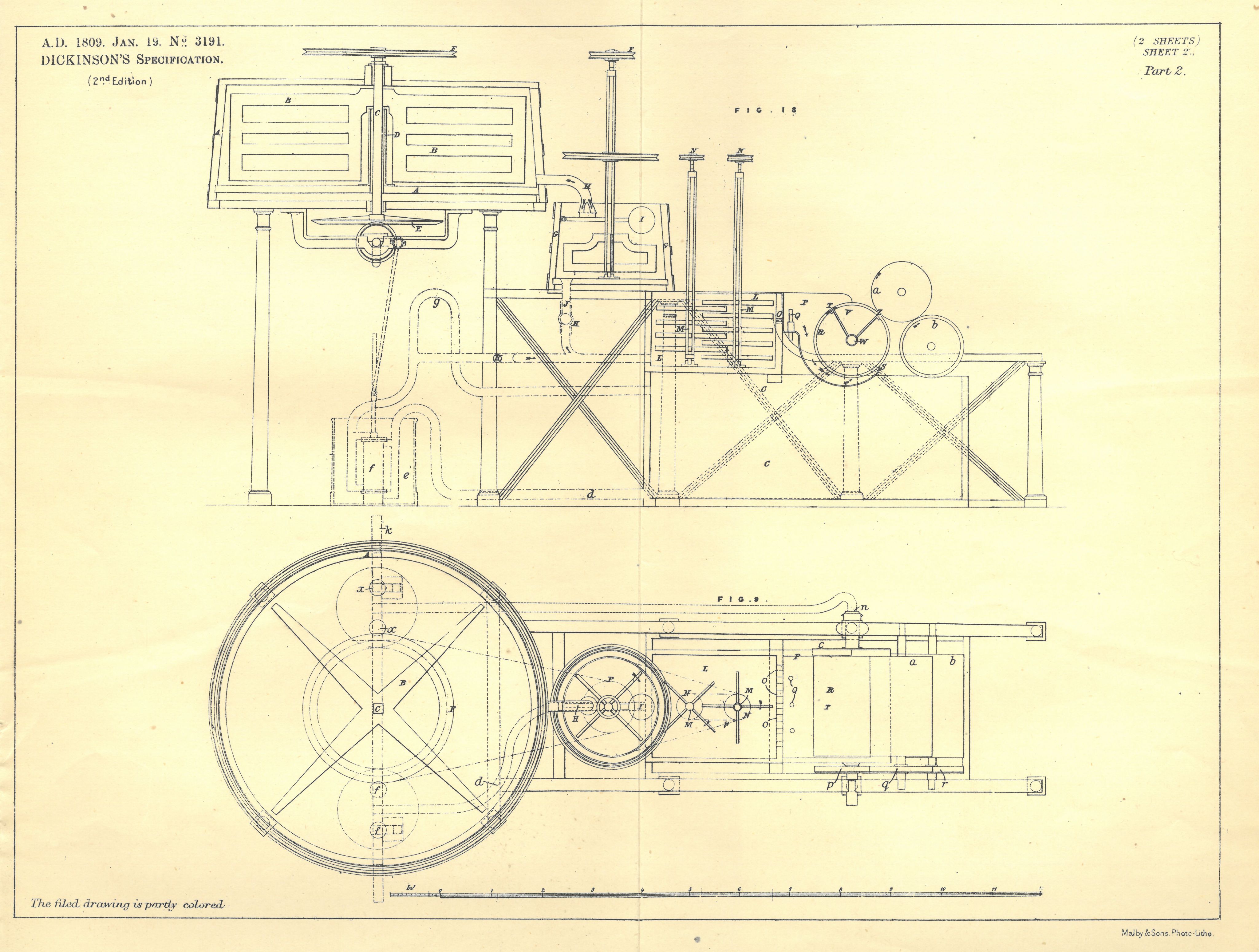

In 1804, John Dickinson first described a different type of paper machine, the Cylinder Mould Machine. His invention was patented in 1809 and became the machine of choice for security papers.

The development of the electrotype process also proved crucial. The watermark would be designed on paper, and then carved out of a block of wax to leave the light parts high, and the dark parts lower. Wax would be coated with a conducting material to deposit copper by electroplating, leaving behind the copper master after the wax had melted. These are known as chiaroscuro, or light-and-shade watermarks.

These complex designs could be soldered or sewn on to the surface of the Cylinder Mould Machine’s cylinders to be reproduced with greater ease.

The process continues today, with further security measures such as holograms and light sensitive particles added as further measures to combat forgery.

Image: the 1809 patent for John Dickinson's Cylinder Mould Machine.

Watermarks have come a long way from the first crude designs, of a few small pieces of wire stitched onto a mould.

Through the chiaroscuro process extraordinary papers can be created that are works of art in their own right, if only they are held up to the light.

In England the papermaker TH Saunders created elaborate 3D watermarks for exhibitions, depicting detailed images of people, places, animals and coats of arms.

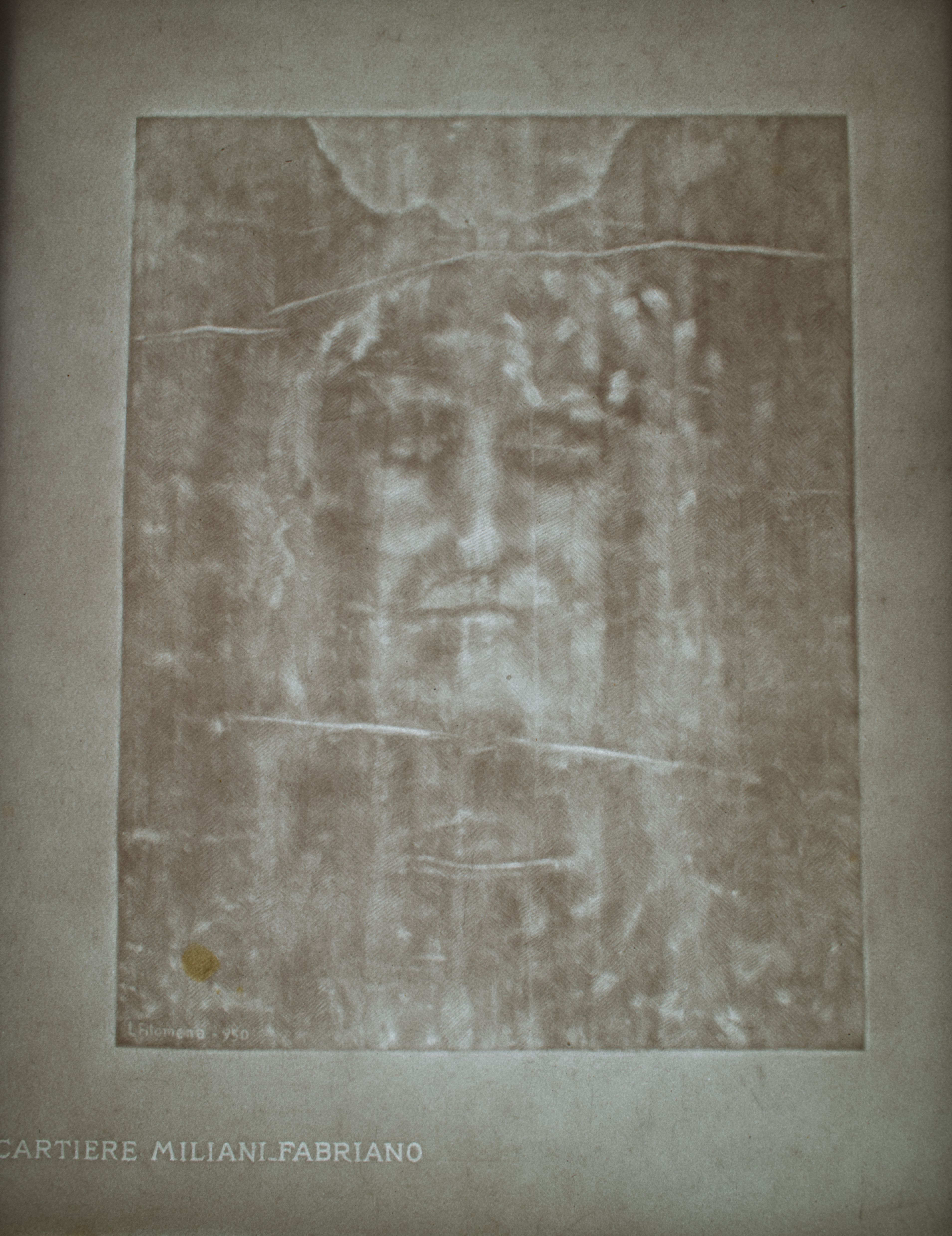

In Fabriano, the very place where the first watermarks were invented, the process is used by paper mills today. Papers are made depicting famous artworks such as Raphael’s Madonnas, and even relics such as the Shroud of Turin.

Previous slide image: Raphael's Madonna della Seggiola, as a chiaroscuro watermark.

Right image: The Shroud of Turin, as a chiaroscuro watermark.

Both watermarks produced by Cartiere Miliani Fabriano.

This exhibition has been supported by a grant from the AIM and Arts Scholars Charitable Trust Brighter Day scheme.

Our thanks go to the Jackson family for their generous donation of watermarks and watermarked papers, many of which are featured in this exhibition.

Frogmore Paper Mill is a working museum operated by the Apsley Paper Trail Trust, which exists to preserve the extensive paper heritage of the Gade Valley and convey the stories of its significant paper past. In 1803 the world’s first paper machine was installed at Frogmore, and the charity still operates a 1902 Fourdrinier Machine for visitors to see and on which artisan papers are produced.

The Michael Stanyon Archive was founded in 1999 and offers a wealth of information about topics relating to papermaking and its history, with a particular focus on the local area and local businesses of John Dickinson & Co and the British Paper Company. You can learn more about the archive at https://www.frogmorepapermill.org.uk/archive/ or by emailing archive@frogmorepapermill.org.uk

The Apsley Paper Trail, registered charity no. 1079008